BEAUFORD DELANEY

Gill & Lagodich have framed paintings by Beauford Delaney for museums and private collections. Several work are shown here.

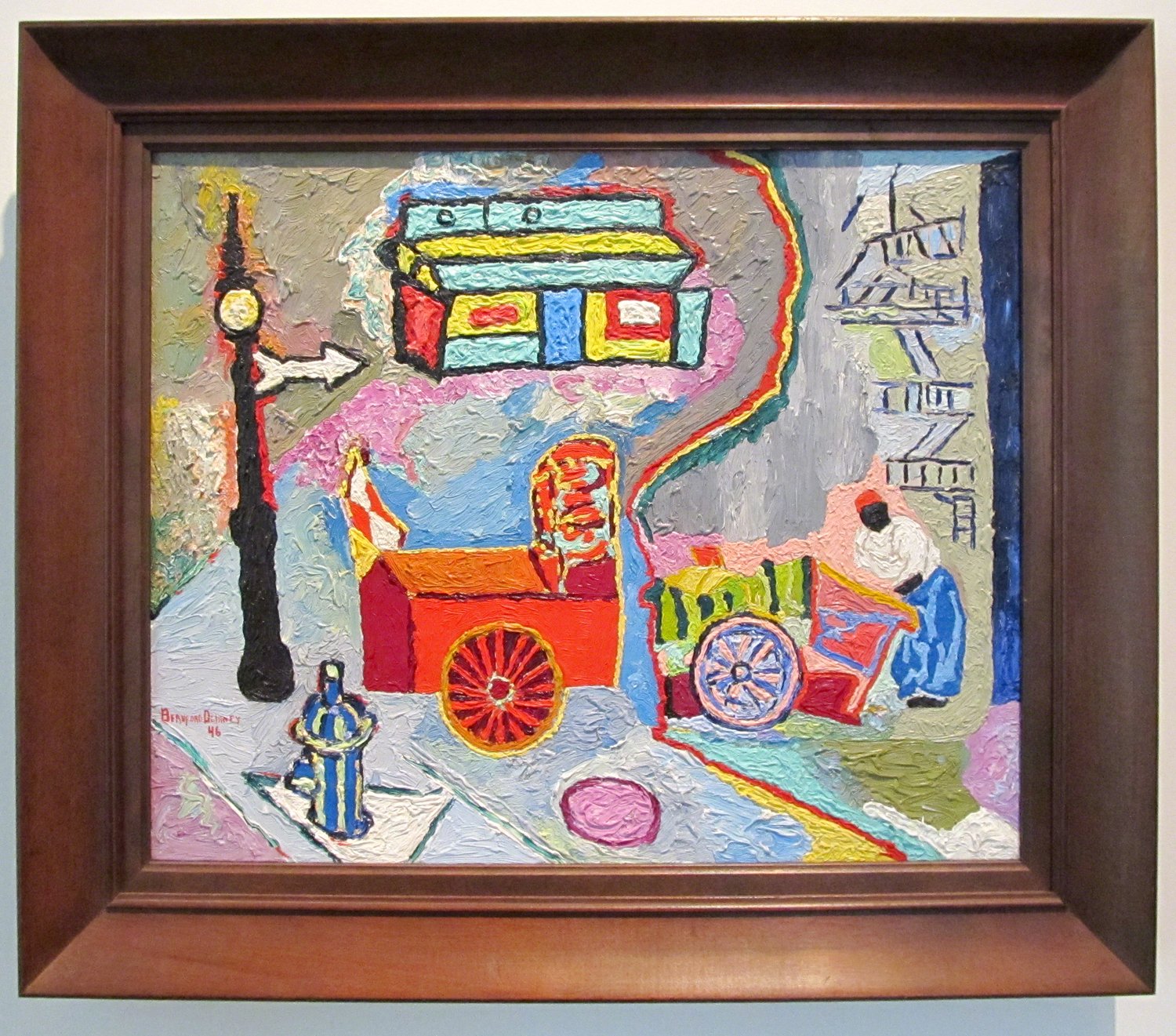

BEAUFORD DELANEY (1901-1979)

Greene Street, oil on canvas, 1946, 16" x 20" Framed by Gill & Lagodich for the Virginia Museum of Fine Art. c. 1920 American stained wood molding frame. molding width 3 in.

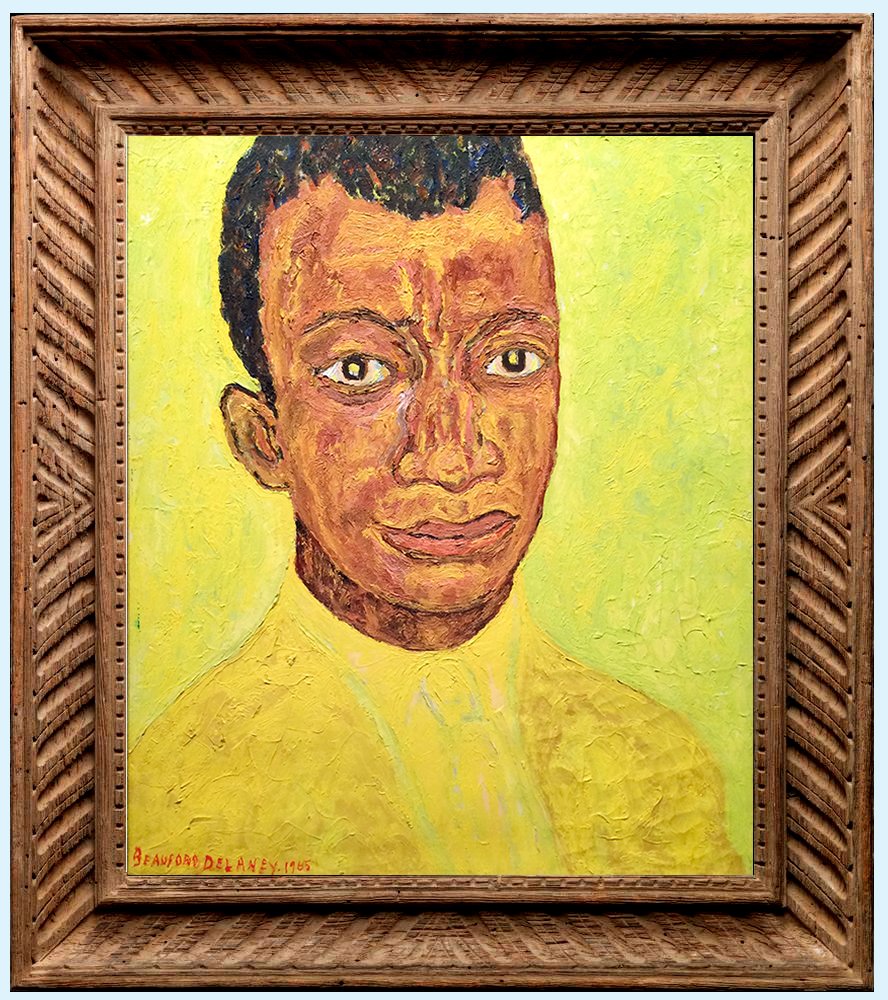

BEAUFORD DELANEY (1901–1979)

Untitled (Village Street Scene), 1948, oil on canvas. Framed by Gill & Lagodich for the Terra Foundation of American Art. Custom-made replica c. 1900 European ebonized molding frame, molding width 2-7/8 in. “The facades, lampposts, and general activity of Greenwich Village were the focus of many works, including Untitled (Village Street Scene), that Beauford Delaney made between 1940 and 1952 while living in New York City. Delaney was captivated by the urban landscape and sought to visually interpret the energy of modern life through brilliant colors, thickly applied paint, and bold, animated lines. Untitled (Village Street Scene) represents the most successful of the artist’s numerous attempts to depict this particular intersection. Its perspective is accurate yet still evocative, while its composition is capacious in ways that allowed Delaney to assemble and reconcile the arrangement of a variety of elements and motifs, that appear frequently in other works of this period, including traffic lights, lampposts, manhole covers, and clouds. Socially, Delaney straddled two worlds. He was part of the burgeoning Harlem Renaissance movement and friendly with artists like Norman Lewis, Jacob Lawrence, Augusta Savage, and Romare Bearden. But desiring to pursue his own particular artistic vision, through his friendship with contemporary artist Stuart Davis, he also became tied to the avant-garde movements of Greenwich Village, where he associated with gallerist Alfred Stieglitz and artists in his circle, such as Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, and Arthur Dove. Moving easily between various groups, Delaney developed a spirited, energetic style for his figural work and cityscapes. The prominence of yellow in Untitled (Village Street Scene) contributes to the work’s liveliness, but also holds a deeper significance: while Delaney was fond of large passages of bright color, he connected most deeply with the color yellow, which held a spiritual significance for him. Untitled (Village Street Scene) is one of the earliest works in his oeuvre that contains a large amount of yellow, covering nearly three-quarters of the canvas, and linking this work to developments later in the artist’s career. Delaney struggled throughout his life with mental health issues and social anxieties pertaining to race and sexuality; for him, the color yellow represented light, healing, and redemption, and he would use it almost exclusively in the portraits and abstract paintings he made in the 1960s and 1970s, near the end of his life.” —Terra Foundation label

Portrait of James Baldwin, 1965, oil on canvas, 25-1/2 x 21-1/4 inches. Framed by Gill & Lagodich for the Chrysler Museum of Art. c. 1930s-40s American painting frame; Heydenryk, New York makers; hand-carved wormy chestnut wood, polychrome (gray wash) finish; molding width: 3-3/4 in. “Intense yellow brings a sacred and redemptive light to Beauford Delaney’s portraits of people he admired, as seen here framing the writer and Civil Rights activist James Baldwin (1924–1987). Though Delaney often exhibited with Harlem Renaissance artists, he preferred the company of intellectual circles in New York’s Greenwich Village. His abstract, colorful, and highly textured paintings found many admirers, including Alfred Stieglitz, Stuart Davis, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Baldwin, who was only a teenager when they first met in 1940. Delaney became a spiritual mentor to the budding writer based on their mutual struggles against poverty, racism, and homophobia, and this portrait, created 25 years later, celebrates their lifelong creative friendship.” —Chrysler Museum label text.

BEAUFORD DELANEY (1901-1979)

Negro Man [Claude McKay], 1944, oil on canvas, 19-1/8” x 16-1/4”. Framed by Gill & Lagodich for LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art.) Period c. 1940s-50s American Modernist frame, gilded and painted wood, molding width 4-1/8”

“Beauford Delaney, one of the most important Black artists of the 20th century, painted this rare portrait of his friend, the well-known Jamaican American writer and poet Claude McKay (1889–1948) when both lived in New York. Delaney’s practice intersects with much of 20th-century American art: the Harlem Renaissance, the circle around modernists Alfred Steiglitz and Georgia O'Keeffe, American urban scene painting, and Abstract Expressionism.

Negro Man [Claude McKay] is an intimate portrait of one of the most influential figures of the Harlem Renaissance. Central to the movement were artists, writers, and intellectuals who represented a new, confident, and vibrant Black expression and self-determination. Many pioneering members of the cultural movement, like Delaney and McKay, were LGBTQ, including Richmond Barthé, Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Alain Locke, and Bessie Smith. In his writings, McKay recorded his radical views on the injustices of Black life in America and his belief in the importance of Black autonomy through socialist revolution.

Delaney renders his friend McKay’s pensive countenance with colorful, thick, expressive brushstrokes that delineate the contours and shadows of his face. Dressed in a bright blue jacket, McKay gazes directly at us; his upper torso fills the canvas, suggesting his powerful presence. Stylistically, the thick brushwork and intense colors reveal Delaney’s appreciation for Van Gogh and the French Fauves. Working from both direct observation and memory, Delaney’s psychologically engrossing portrait captures his sitter’s temperament through details of clothing and expression, set against a textured abstract background.

Delaney emigrated to Paris in the 1950s, following his friend, writer James Baldwin, and joining a community of Black American writers, artists, and musicians who found Paris more accepting and less discriminatory to Blacks and homosexuals. In Paris his work turned more abstract and gestural, which would be his prevailing style for the remainder of his life.” —LACMA curatorial notes