Sometimes, a Frame Is Worth a Thousand Words, By Lucie Young, The New York Times, Thursday March 3, 1994, Section C, page 1 + 10 (National Edition page 46 + 53)

LIKE American furniture, antique American picture frames have undergone a cycle of rejection and reappraisal. Ten years ago, the Museum of Modern Art banished opulent gilt frames from all its galleries and rehung its artworks in virtually identical L-shaped borders. "The feeling was that the antique frames were a distraction," said Fred Coxen, a former supervisor of the museum's exhibition and production department.

While Mr. Coxen believes art is seen more directly this way, he admits to simply enjoying the frame as a piece of period ornamentation. And he has placed a few around his Manhattan apartment -- minus the art.

He's in good company.

In 1990, after a popular exhibition on the subject, the Metropolitan Museum of Art installed 30 American antique frames in a permanent display in its Henry R. Luce Center for the Study of American Art. Carrie Rebora, the center's manager, said, "Curators have begun to think of frames in and of themselves as true works of art, which was certainly not the case 10 to 15 years ago."

Those interested in collecting these neglected samples of American craft work will look long and hard for books on the subject. About the only resource is talking to dealers at flea markets and at frame houses, which mostly supply art collectors. But the Manhattan team of Gill & Lagodich is coming to the rescue.

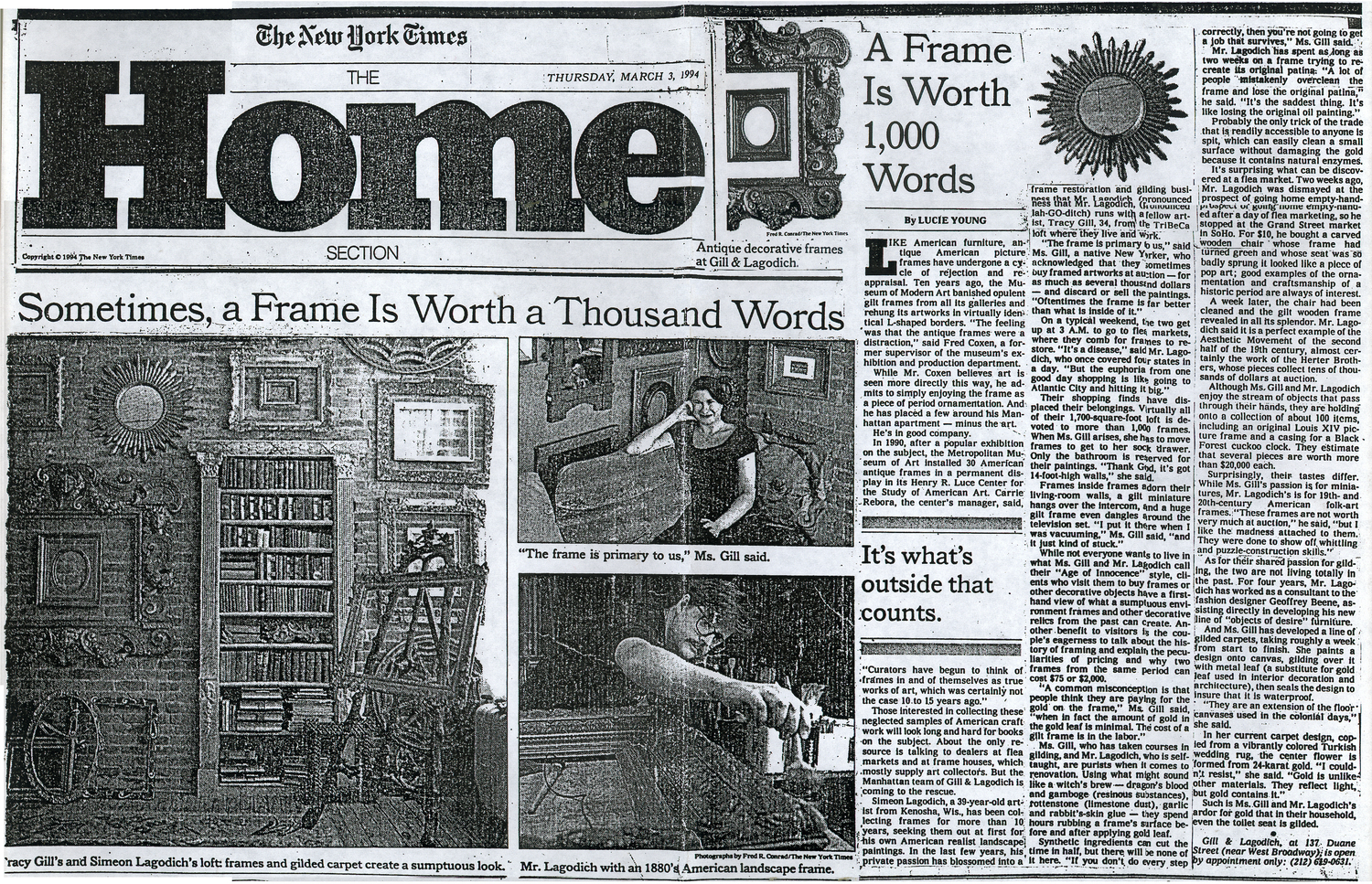

Simeon Lagodich, a 39-year-old artist from Kenosha, Wis., has been collecting frames for more than 10 years, seeking them out at first for his own American realist landscape paintings. In the last few years, his private passion has blossomed into a frame restoration and gilding business that Mr. Lagodich, (pronounced lah-GO-ditch) runs with a fellow artist, Tracy Gill, 34, from the TriBeCa loft where they live and work.

"The frame is primary to us," said Ms. Gill, a native New Yorker, who acknowledged that they sometimes buy framed artworks at auction -- for as much as several thousand dollars -- and discard or sell the paintings. "Oftentimes the frame is far better than what is inside of it."

On a typical weekend, the two get up at 3 A.M. to go to flea markets, where they comb for frames to restore. "It's a disease," said Mr. Lagodich, who once covered four states in a day. "But the euphoria from one good day shopping is like going to Atlantic City and hitting it big."

Their shopping finds have displaced their belongings. Virtually all of their 1,700-square-foot loft is devoted to more than 1,000 frames. When Ms. Gill arises, she has to move frames to get to her sock drawer. Only the bathroom is reserved for their paintings. "Thank God, it's got 14-foot-high walls," she said.

Frames inside frames adorn their living-room walls, a gilt miniature hangs over the intercom, and a huge gilt frame even dangles around the television set. "I put it there when I was vacuuming," Ms. Gill said, "and it just kind of stuck."

While not everyone wants to live in what Ms. Gill and Mr. Lagodich call their "Age of Innocence" style, clients who visit them to buy frames or other decorative objects have a firsthand view of what a sumptuous environment frames and other decorative relics from the past can create. Another benefit to visitors is the couple's eagerness to talk about the history of framing and explain the peculiarities of pricing and why two frames from the same period can cost $75 or $2,000.

"A common misconception is that people think they are paying for the gold on the frame," Ms. Gill said, "when in fact the amount of gold in the gold leaf is minimal. The cost of a gilt frame is in the labor."

Ms. Gill, who has taken courses in gilding, and Mr. Lagodich, who is self-taught, are purists when it comes to renovation. Using what might sound like a witch's brew -- dragon's blood and gamboge (resinous substances), rottenstone (limestone dust), garlic and rabbit's-skin glue -- they spend hours rubbing a frame's surface before and after applying gold leaf.

Synthetic ingredients can cut the time in half, but there will be none of it here. "If you don't do every step correctly, then you're not going to get a job that survives," Ms. Gill said.

Mr. Lagodich has spent as long as two weeks on a frame trying to recreate its original patina. "A lot of people mistakenly overclean the frame and lose the original patina," he said. "It's the saddest thing. It's like losing the original oil painting."

Probably the only trick of the trade that is readily accessible to anyone is spit, which can easily clean a small surface without damaging the gold because it contains natural enzymes.

It's surprising what can be discovered at a flea market. Two weeks ago, Mr. Lagodich was dismayed at the prospect of going home empty-handed after a day of flea marketing, so he stopped at the Grand Street market in SoHo. For $10, he bought a carved wooden chair whose frame had turned green and whose seat was so badly sprung it looked like a piece of pop art; good examples of the ornamentation and craftsmanship of a historic period are always of interest.

A week later, the chair had been cleaned and the gilt wooden frame revealed in all its splendor. Mr. Lagodich said it is a perfect example of the Aesthetic Movement of the second half of the 19th century, almost certainly the work of the Herter Brothers, whose pieces collect tens of thousands of dollars at auction.

Although Ms. Gill and Mr. Lagodich enjoy the stream of objects that pass through their hands, they are holding onto a collection of about 100 items, including an original Louis XIV picture frame and a casing for a Black Forest cuckoo clock. They estimate that several pieces are worth more than $20,000 each.

Surprisingly, their tastes differ. While Ms. Gill's passion is for miniatures, Mr. Lagodich's is for 19th- and 20th-century American folk-art frames. "These frames are not worth very much at auction," he said, "but I like the madness attached to them. They were done to show off whittling and puzzle-construction skills."

As for their shared passion for gilding, the two are not living totally in the past. For four years, Mr. Lagodich has worked as a consultant to the fashion designer Geoffrey Beene, assisting directly in developing his new line of "objects of desire" furniture.

And Ms. Gill has developed a line of gilded carpets, taking roughly a week from start to finish. She paints a design onto canvas, gilding over it with metal leaf (a substitute for gold leaf used in interior decoration and architecture), then seals the design to insure that it is waterproof.

"They are an extension of the floor canvases used in the colonial days," she said.

In her current carpet design, copied from a vibrantly colored Turkish wedding rug, the center flower is formed from 24-karat gold. "I couldn't resist," she said. "Gold is unlike other materials. They reflect light, but gold contains it."

Such is Ms. Gill and Mr. Lagodich's ardor for gold that in their household, even the toilet seat is gilded.

Gill & Lagodich, at 137 Duane Street (near West Broadway), is open by appointment only: (212) 619-0631.